Scientists investigate presence of ancient deep-sea microplastics

Marine scientists are seeking to solve a deep-sea microplastics mystery after finding evidence of manufactured plastics buried in the seabed sediment.

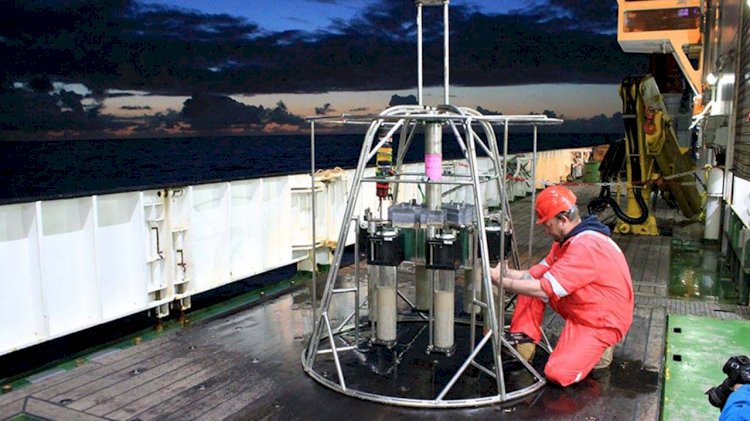

Researchers from the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban previously found traces of microplastics – small pieces of plastic less than 5 millimetres in size – at 2,200 metres below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, near to the Rockall Trough off the west coast of Scotland.

But their samples, known as sediment cores, have now revealed plastic particles 10cm below the seabed in layers of sediment that were hundreds of years old, leaving the researchers with more questions to answer.

Dr Winnie Courtene-Jones, who is now science lead on the all-female marine plastic pollution project eXXpedition, carried out the sampling as part of her PhD at SAMS. She said:

“We found a greater abundance of microplastics nearer the top of the sediment, as we expected, as these layers build up over time. However, we found plastic throughout 10cm depth of sediment analysed. The layers of sediment down to around four centimetres were around 150 years old, so based on that discovery alone, plastics were in the sediment long before they were mass produced on land! It just didn’t add up.”

The researchers then turned their attention to the gaps between the sediment grains, or ‘pores’, and burrows created by deep-sea dwelling worms such as the peanut worm, spoon worm or bamboo worm.

In a newly published paper in Marine Pollution Bulletin, the authors from SAMS and the University of the West of Scotland have hypothesised that this so-called sediment reworking could allow the microscopic plastic to move through the pores, down through the sediment.

Prof Bhavani Narayanaswamy of SAMS, a co-author on the paper, said:

“Plastic manufacturing boomed during the 1940s-50s, yet from this study microplastics can be detected in sediments dating from well before the 1890s. More work is required to understand these processes and find out how the microplastics are getting to these depths and what their effect might be on the sediment. Ultimately the microplastics that we detect in the sediment have originated from the fragmentation of larger plastic items used on land.”

The scientists measured the presence of the isotope Lead-210, which decays over time, to determine the age of each sediment layer. The samples were collected in 2017 on a combined Extended Ellett Line/OSNAP project cruise.