Posidonia marine seagrass can catch and remove plastics from the sea

Underwater seagrass in coastal areas appear to trap bits of plastic in natural bundles of fibre known as "Neptune balls," researchers said.

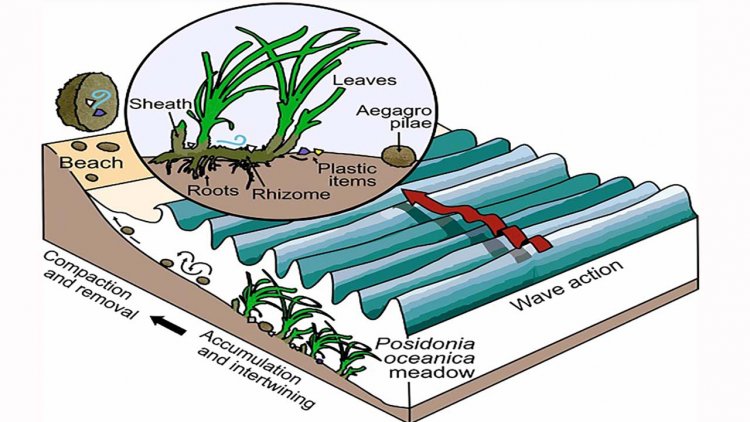

Posidonia oceanica seagrass –an endemic marine phanerogam with an important ecological role in the marine environment- can take and remove plastic materials that have been left at the sea, according to a study published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The study describes for the first time the outstanding role of the Posidonia as a filter and trap for plastics in the coastal areas, and it is pioneer in the description of a natural mechanism to take and remove these materials from the sea.

The Posidonia oceanica makes dense prairies that make a habitat with a great ecological value (nutrition, shelter, reproduction, etc.) for marine biodiversity. As part of the study, the team analysed the trapping and extraction of plastic in great seagrasses of the Posidonia in the coasts of Majorca.

Anna Sànchez-Vidal, member of the Department of Ocean and Earth Dynamics of the UB, notes:

“Everything suggests that plastics are trapped in the Posidonia seagrass. In the grasslands, the plastics are incorporated to agglomerates of natural fiber with a ball shape –aegagropila or Posidonia Neptune balls- which are expulsed from the marine environment during storms.”

“According to the analyses, the trapped microplastics in the prairies of the Posidonia oceanica are mainly filaments, fibers and fragments of polymers which are denser than the sea water such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET)."

Posidonia aegagropilae are expelled from the prairies during periods of strong waves and a part ends up piled in the beaches. Although there are no studies that quantify the amount of aegagropilae expelled from the marine environment, it is estimated that about 1,470 plastics are taken per kilogram of plant fibre, amounts which are significantly higher than those captured through leaves or sand. As researcher Anna Sànchez-Vidal says:

“We cannot completely know the magnitude of this plastic export to the land. However, first estimations reveal that Posidonia balls could catch up to 867 million plastics per year”.

The polluting footprint of plastics that come from human activity is a serious environmental problem affecting coastal and ocean ecosystems worldwide. Since plastics were created massively in the 20th century fifties, these materials have been left and accumulated at the sea –seafloors act as a sink for microplastics— and are transported by ocean currents, wind and waves.

The new ecosystemic service of the Posidonia described in the article has a significant value in a marine area such as the Mediterranean –with high quantities of floating plastic and in the seafloors— and with Posidonia seagrass that can occupy large areas up to forty meters deep.

The experts conclude:

“This is why we need to protect and preserve these vulnerable ecosystems. However, the best environmental protection strategy to keep oceans free of plastic is to reduce landfills, an action that requires to limit its use by the population.”

The article’s first author is the tenure-track 2 lecturer Anna Sànchez-Vidal, from the Research Group on Marine Geosciences of the Faculty of Earth Sciences of the UB. Other authors of the study are the experts Miquel Canals, William P. de Haan and Marta Veny, from the Research Group on Marine Geosciences of the UB, and Javier Romero, from the Faculty of Biology and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio) of the UB.